~ Fans are getting lost in the eye candy of Spider-man: Into the Spider-verse. Critics love the art, fans enjoy the easter eggs, and Sony is seeking a patent for the animation. Spider-verse has so much cultural representation The Root praised it for being extra-Black. Despite, or perhaps because of these achievements, Miles’ story is being overshadowed. Spider-verse bases it’s story on a popular crossover event, and only uses parts of Miles’ origin. As a friend pointed out, the original Japanese trailer didn’t even show Miles’ face, and made it seem Spider-verse was about Peter Parker. The torch is passed to Miles, but he doesn’t light the fire. He carries on the work others have started, but that’s what he’s always done. To celebrate Black History Month I’m exploring the Black history beneath Spider-verse, and the story behind Miles, aka Lucky #42.

“When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves, or figments of their imagination – indeed, everything and anything except me.”

– Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

#42 has a significance Spider-verse doesn’t explain. We see how Miles got his powers, but not why he chose to be Spider-Man. The answer lies in comics, literature, and American schools. I’ve summarized it out of necessity, because Miles is so often misunderstood. GodzillaMendoza’s Spider-Man YouTube channel is one example:

Into the Spider-Verse – The Problem With Miles, GodzillaMendoza, 2017

This is an informed fan, how could he be so wrong about Miles? I think what distances him, and many others from Miles is formal education. Understanding Miles is a paradox. His obstacles are drawn from poor communities while his story pulls from academic civil rights literature. Ignorance of these influences makes Miles invisible, even if you’ve seen Spider-verse ten times, or read the comics a hundred times. Its time more people see the invisible Spider-Man.

MILES (V.O.)

OK, let’s do this one last time, yeah? For real this time. This is it.

Lord, Phil. Rotham, Rodney. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse. Screenplay. 2018.

The Invisible Truth

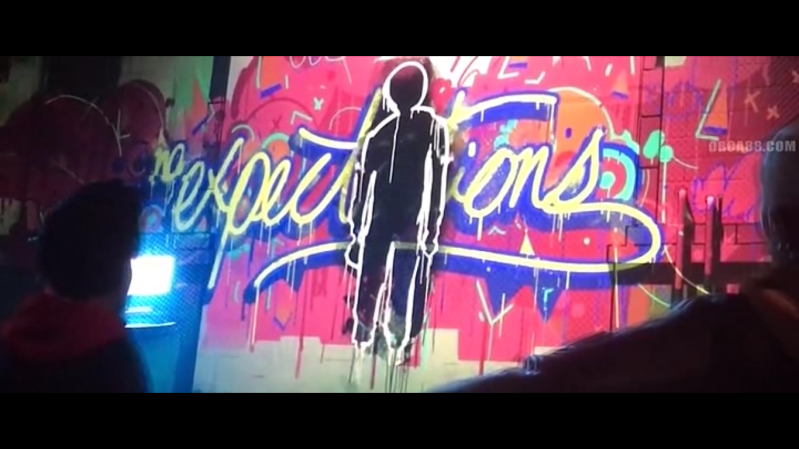

Peter Parker was the first Amazing Spider-Man, and Miles Morales was the first invisible one. His powers allude to the 1952 novel Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison. The novel is a complex psychological journey that elevated the civil rights movement and defined the Black experience for modern American literature. The main character isn’t literally invisible, his story is a nuanced metaphor about why people choose to not see the Invisible Man for who he really is. His Blackness defines him, he is judged as competition or commodity, while merits of his character are invisible. Privileged fans see Miles the same way; they define him by race, calling him a “a color swap of a different character,”. Because Miles’ problems are predominately Black issues, privileged readers can’t relate. Ellison knew white readers would have the same issue with Invisible Man, which is why never tells the reader the narrator’s name. By doing this Ellison makes the Invisible Man partially invisible to the reader. He forces the reader to examine their own prejudices as they read, subverting expectations by using the novel as a mirror. Miles’ story parallels events in Invisible Man; an underprivileged Black student strives for an education, gets it by luck more than merit, and uses his invisibility to combat violent oppression. Miles’ story is a reference to literary history and the Black experience. Spider-verse illustrates that in Miles’ graffiti art. In the screenplay, which thank God Sony made publicly available, Miles’ graffiti is:

A STRIKING PIECE, built around Miles silouette with nothing painted inside it. A BLANK. “No Expectations” written above.

Lord, Phil. Rotham, Rodney. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse. Screenplay. 2018.

“No Expectations” demonstrates Miles’ feelings towards his school, family, and race. Notably, Miles’ outline is painted black in the final cut rather than “nothing painted inside it.” like the screenplay says. The Black experience is visible in Spider-verse, but controversial events from Miles’ story aren’t. I asked the writers of Spider-verse about this, and I’ll update if they answer. But I’m inclined to believe the writers were told to remove them. Miles’ real story is highly controversial but that should be the whole point; Miles was born from activism.

How Miles was colored by controversy

Sitting in a Tree, Marvel comics

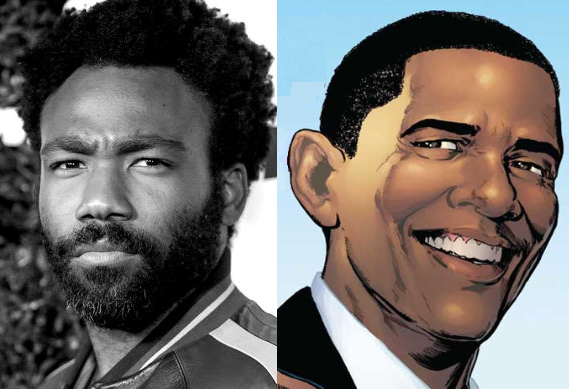

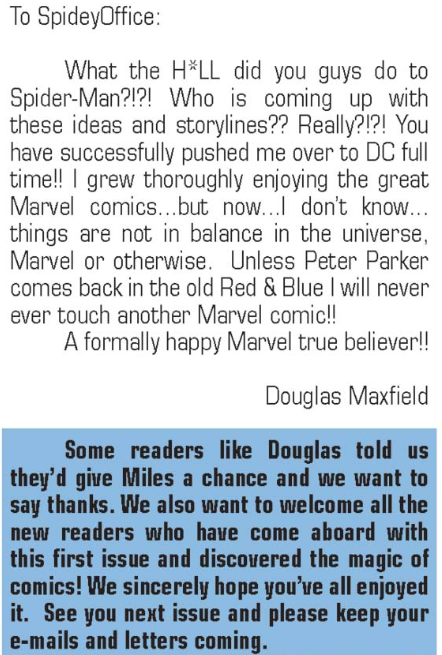

Miles Morales was created in 2011 by Brian Bendis and Sara Pichelli, they were inspired by two Black icons: President Barack Obama, and Avant-garde artist Donald Glover. Miles bears a close resemblance to President Obama in the comics, and I’d venture a slight one to Glover in Spider-verse. When Miles was created conservative attacks were constant, one homophobic right-wing host called Miles gay and blamed First Lady Obama for his creation. It wasn’t just pundits, Miles faced hateful backlash from many longtime fans. Rather than hide the controversy, Marvel printed the angry letters in Miles’ debut issue, they embraced it.

Ultimate Comics: Spider-Man Marvel Comics

These kinds of letters threatened the project. Bendis said seeing Donald Glover in Spider-Man pajamas encouraged the team to continue. Bendis and Pichelli drew inspiration from Black artists, political figures, and issues, not unlike Ellison did in Invisible Man. It was sincere cultural appreciation rather than superficial appropriation, but that was a problem for fans using comics as an escape from reality. Spider-verse doesn’t have that problem, it doesn’t talk about the police brutality debate, or challenge the rise of white nationalism. Spider-verse diverges from the source material, but that might have been a mistake, Invisible Man has been called the parable of our time:

“Invisible Man” ends with the protagonist being chased by policemen during a riot in Harlem, and falling into a manhole in the middle of the street.

…

I revisit the final pages of “Invisible Man” and think of how many things that once existed above ground in our country might now become trapped beneath the surface.

Smith, Clint, The New Yorker, 2016,

Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” as a Parable of Our Time

Ultimate Comics: Spider-Man Marvel Comics

Spider-verse is accessible entertainment, not a divisive debate. But that debate fueled Miles’ popularity in the first place. A Black Spider-Man modeled after the first Black president was a welcome answer to the racist allegations of the birther movement. Bendis and Pichelli made it very clear Miles’ roots are cultural and sociopolitical. Miles is colored by the Black struggle in America, which never stopped. Spider-verse is colorful, but it avoids that discussion. By doing so, it inadvertently gentrifies Miles’ father.

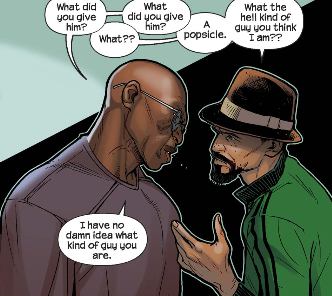

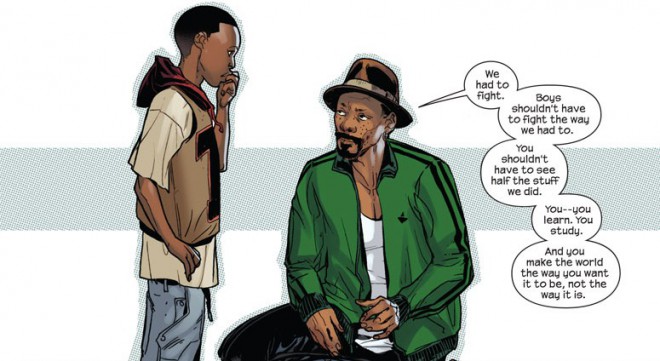

Jefferson Davis: NYPD, Bigot, Ex-Con

In Spider-verse, Jefferson is almost always in uniform. In the comics he was NYPD, but also an ex-con and a hateful bigot. Jefferson sees mutants as the other, and that bigotry is a constant burden for Miles. That burden is highly relevant considering public opinion towards racial profiling. Miles protects the weak from the powerful as a response to his father’s prejudice. When Jefferson learned he was going to be a father, he feared the day his son would discover his criminal record. In a powerful scene Jefferson reveals his shame to Miles, the one person he wanted to keep it from. In a rare scene of good parenting, Jefferson says most people commit crimes because they see no other way. Miles learns the importance of perspective, that views and people change. His father Jefferson embraced bigotry but rejected crime, his Uncle Aaron embraced crime and rejected bigotry, Miles develops his worldview in response to their flaws. GodzillaMendoza oversimplifies this dynamic saying “one was a cop the other a criminal.” but he ignores the nuance. The Davis brothers are a case study on the effects of systemic racial oppression in the American justice system. Jefferson even accuses Aaron of giving Miles drugs, while Aaron sees Jefferson as part of the broken criminal justice system.

Ultimate Comics: Spider-Man Marvel comics

Story-wise, Jefferson’s criminal record is pivotal; it allowed him to go undercover, and eventually join Nick Fury at SHIELD. Jefferson’s SHIELD arc references the privatization of the American military. Like all military support, Jefferson’s mercenary work stems from his desire to protect his family. Nick Fury promised Miles would be protected if Jefferson joined SHIELD. Jefferson knew Miles was Spider-Man by then, and constantly feared for his safety. Jefferson displays deep fatherly love, but he’s also a critical caricature on the militarization of American police. Police chiefs warn that police brutality is still being encouraged. Jefferson’s story in the original comics acknowledges those issues, it’s a shame Spider-verse didn’t.

Ultimate Comics: Spider-Man Marvel comics

I criticize fans like GodzillaMendoza for oversimplifying Miles, but I’m doing the same with Jefferson here, he is very complicated. Spider-verse doesn’t focus on Jefferson, and that’s not bad per se. The movie is a standalone universe and Jefferson is simplified to make room for Spider-verse’s story. Real evils like racism, police brutality and the military industrial complex don’t fit in a feel good kids’ movie. Instead, Spider-verse defines Miles’ relationship with police by his dad being an officer. His tagging is a crime of self expression, rather than surviving systemic oppression. Spider-verse portrays police as a single paternal figure rather than an amoral entity. Therein lies the problem, Spider-verse’s Jefferson puts government above criticism, or perhaps more relevant, above the law. Thankfully, Miles was left intact, and that saves Spider-verse.

How Spider-verse saved Miles (Spoilers)

Ultimate Comics: Spider-Man Marvel comics

Spider-verse removes controversial themes but saves Miles’ character. It accomplishes this by keeping key emotions from the comics but changing the subject matter. Jefferson goes from bigot to Spider-Man hater. The hate is still there, but from a less damning source. Jefferson isn’t hateful from bigotry, he’s just jealous:

JEFFERSON: Spider-Man. I mean this guy swings in once a day zip zap zop in his little mask and answers to no one, right? (…) meanwhile my guys are out there, lives on the line- (…) no masks, we show our faces. Accountability. (…) You know, with great ability comes great accountability-

MILES: That’s not even how the saying goes, Dad-

JEFFERSON –I do like his cereal though, I’ll give him that

Lord, Phil. Rotham, Rodney. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse. Screenplay. 2018.

Jefferson feels underappreciated while the cereal mascot gets credit. His love for Miles is fierce, but the impact of his flaws are trivial. Miles is similarly altered, he’s more ashamed of his powers ruining his “game” than he is about death of Peter Parker. He barely has time to mourn Peter Parker’s death before Peter B. Parker replaces him. We don’t see Miles reluctantly transform into a vigilante, instead he starts as one. He tags and leaves shoelaces untied as “a choice.” He talks about being with “the people” and thinks his charter school is elitist. Spider-verse skips the dark themes and focuses on the best intentions of it’s characters. Kingpin may be the villain, but he just wants his family back. This tonal shift has a bright side, Aaron/Prowler’s connection with Miles is deeper. His love for Miles stops him from following orders, and he becomes a martyr of sorts. In the comics Aaron isn’t a doting Uncle for long, and Miles isn’t defenseless.

In the comics Miles doesn’t want to be Spider-Man, his fear overrides his beliefs at first. Aaron is a perpetual shadow over Miles, a reminder of what he would’ve become if his self-interest had pushed him to the dark side. Spider-verse inverts Mile’s influences, Peter Parker’s death is downplayed and Uncle Aaron becomes the martyr. Notably, Spider-verse made the Black life matter. The writers should be applauded for that representation, but the Spider-verse isn’t without racist stereotypes. Peni Parker is the main offender, but others have written on that. Miles is done well, Spider-verse preserves his character and he gives the movie the weight it needs to avoide being a superficial superhero flick. Miles encourages the audience to “wear the mask”, and enlists us as heroes, without telling us the cause. Unlike Black Panther, Spider-verse doesn’t support a cause outright. It hints at that cause with #42, but we never see who gave Miles that number.

MILES (V.O.)

I never thought I’d be able to do any of this stuff. But I can. Anyone can wear the mask. You can wear the mask. If you didn’t know that before, I hope you do now.

Lord, Phil. Rotham, Rodney. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse. Screenplay. 2018.

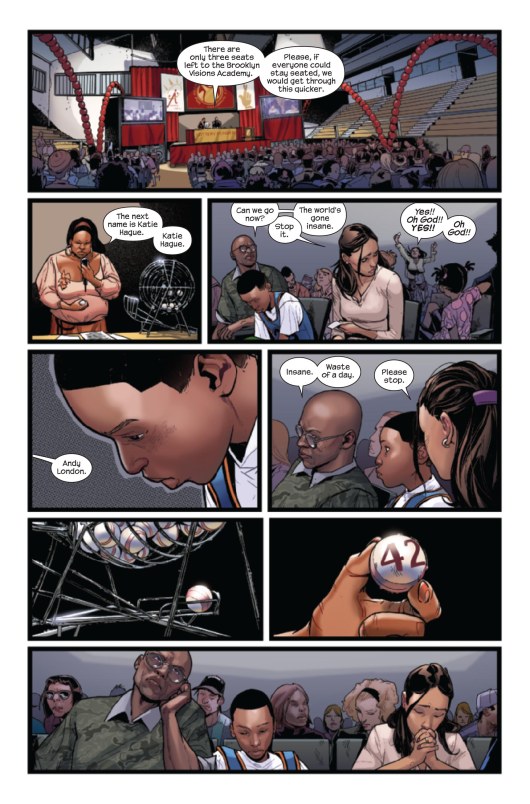

What #42 means to Miles Morales

Ultimate Comics: Spider-Man Marvel comics

42 was Miles’ number in his charter school lottery. Since they are public schools, charters are required by law to hold a student lottery when they don’t have enough spots. Miles wins the final spot at Brooklyn Visions Academy, but its not a victory, its a grim reminder that most of America’s failing schools are in poor communities. For children from poor families, winning a lottery is the only way to escape dropout factories and the increased threat of violence. Spider-verse mentions the lottery once, Miles calls it stupid, and Jefferson argues his admission was earned:

MILES: I’m only here ‘cause I won that stupid lottery–

JEFFERSON: No way. You passed the entry test just like everybody else, ok!

Lord, Phil. Rotham, Rodney. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse. Screenplay. 2018.

The entire point of the lottery was Miles didn’t earn anything. His number got drawn, test results didn’t determine admittance. The #42 was used to convey the importance of that. It references Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, where #42 is famously considered: “The answer to life, the universe, and everything.” Jefferson should be disgusted by the lottery, there’s no reason for him to pretend Miles earned his spot. That was Miles’ iconic introduction: walking to a charter lottery with his parents. Its a problem underprivileged minorities still experience. Luck decides who succeeds and who doesn’t, children’s futures are literally gambled for. That scenario causes Miles to develop his defining character trait, empathy.

Ultimate Comics: Spider-Man Marvel comics

Miles is a hero because of how he reacts to injustice. When Miles wins the lottery Rio Morales celebrates for her son, like any mother would. She embraces him and says, “Oh, my God, you have a chance.” Which means before now, he didn’t. Miles knows that, and rather than celebrate “winning” he mourns for those who “lost”. His first response is to ask, “Should it be like this?” Miles thinks like an activist, he doesn’t join in on the game society is playing. While his father complains and his mother prays, Miles asks how things should be. The charter lottery is why Miles became Spider-Man; he learned first-hand that Superman wasn’t coming.

“One of the saddest days of my life was when my mother told me ‘Superman’ did not exist. I was a comic book reader… even in the depths of the ghetto you just thought he’s coming I just don’t know when… She thought I was crying because it’s like Santa Claus is not real. I was crying because no one was coming with enough power to save us.”

Geoffrey Canada, Education Reformer, Waiting for Superman, 2010

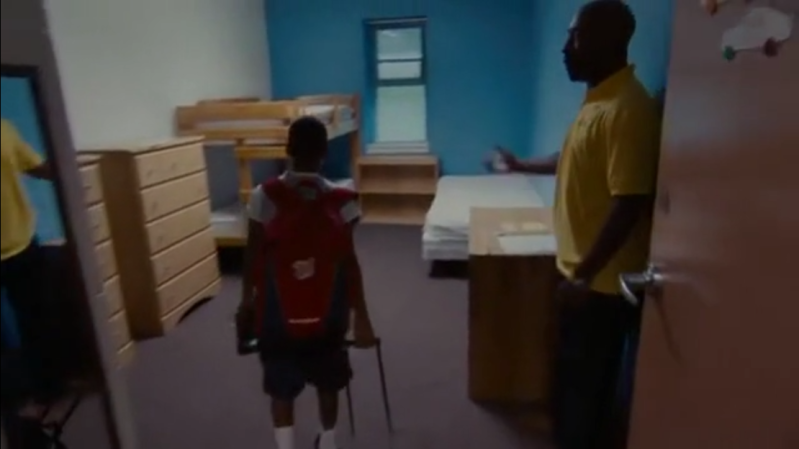

Waiting for Superman is a 2010 documentary that interviews poor families and follows them into their charter school lotteries. Most are denied admission, and the audience sees the fallout. Superman shows crying children and single mothers, widowed by violence or drugs. The title comes from the above quote by Geoffrey Canada, a self proclaimed “angry black man”, more commonly known as the founder and CEO of Harlem’s Children Zone. The Harlem Children’s Zone is “a pioneering nonprofit organization committed to ending generational poverty in Central Harlem.” Waiting for Superman focuses on these types of organizations and ends with a boy choosing a bunk at a charter school, Miles picks the same one in the comics.

-

The final scene of Waiting for Superman -

Miles and Ganke in Marvel comics

Following the Invisible Man

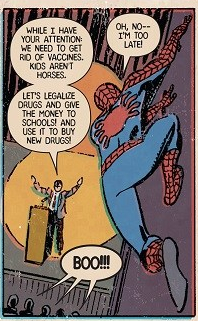

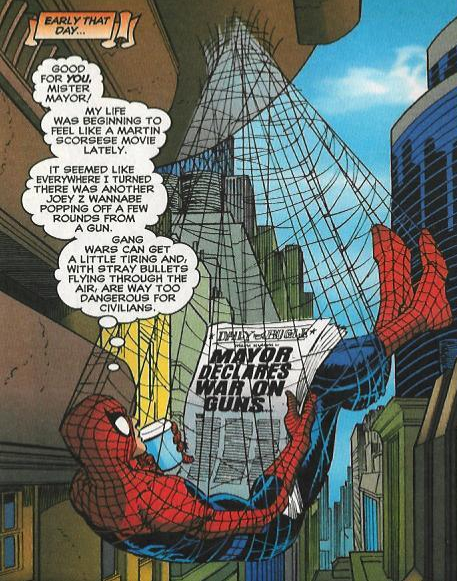

Spider-verse has enjoyed record breaking success because it captures Miles’ spirit. Fans love Miles partially because he deals with causes that are grossly under-represented. Black History Month is the time to honor champions of those causes: Ralph Ellison, President Obama, Geoffrey Canada and Donald Glover all wore the mask before Miles did. The web that ties them together: Education. Spider-Man’s motto: “With great power comes great responsibility,” gains a new meaning when we consider that knowledge is power. Miles’ story reiterates our responsibility to empower the next generation. Spider-verse doesn’t focus on that, but is that how it should be? Spider-Man ended an anti-vax speech by punching Mysterio, he supported gun control, and argued against corruption. None of that was Miles either, that was all Peter Parker. This was years ago, and none of those were controversial acts. Believe it or not we’re going backwards, ignorance is winning.

-

Mysterio as an Anti-Vaxer -

Spider-Man supports gun control -

Deadpool and Spider-Man talk corruption

“The status quo can be changed but it takes a lot of outrage and a lot of good examples.”

Bill Gates, CEO/Philanthropist, Waiting for Superman, 2010

Spider-verse has demonstrated some incredible creative ability, and as Jefferson says “With great ability, comes great accountability.” Miles is the perfect hero to tackle education reform, because he asks how things should be. The next movie should have that story, one relevant to today’s injustices and shot through with nods to Black history. As Spider-verse makes the transition to digital and DVD, it should follow Black Panther’s example. The special features should include the Black history that inspired Miles, and information on how to support organizations like Harlem Children’s Zone. Like Ellison’s Invisible Man, Miles’ Spider-Man should force us to look in the mirror. For those brave enough, I’ve included Waiting for Superman in it’s entirety below. Its only a couple hours, it completely free, and will likely bring some to tears. Injustice is hard to watch, but we shouldn’t unplug from reality. That’s what #42 is all about, acknowledging the problems and asking how it should be. Kids at failing schools are still waiting for Superman, and for them, we all need to be Spider-Man.

Best Documentary – 2010 Sundance Film Festival – Waiting for Superman

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed this work and want to help more people see the invisible Spider-Man, please like and share.

Until next time, GG

~Dan